simulatr on your laptop

example-local.RmdHere we walk through a simple example of building a

simulatr specifier object, checking and running the

simulation locally, and visualizing the results. We consider estimating

the coefficients in a linear regression model via ordinary least squares

and lasso, varying the number of samples.

1. Assemble simulation components

-

parameter_grid. The problem parameters will be the sample sizen, the dimensionp, the number of nonzero coefficientss, and the value of each nonzero coefficientbeta_val. In this simulation, we will only varyn. We could have therefore put the remainder of the parameters infixed_parameters, but we avoid this to have all problem parameters inparameter_grid.parameter_grid <- data.frame( n = c(25, 50, 75, 100), # sample size p = 15, # dimension s = 5, # number of nonzero coefficients beta_val = 3 # value of nonzero coefficients )Next, we want to create the ground truth inferential targets based on the problem parameters. In this case, the inferential target is the coefficient vector. We define a function

get_ground_truth()that takes as input three of the problem parameters and outputs the coefficient vector:get_ground_truth <- function(p, s, beta_val){ beta <- numeric(p) beta[1:s] <- beta_val list(beta = beta) }We can append these ground truth inferential targets to

parameter_gridusing the helper functionadd_ground_truth():parameter_grid <- parameter_grid |> add_ground_truth(get_ground_truth)Let’s take a look at the resulting parameter grid:

parameter_grid #> # A tibble: 4 × 5 #> n p s beta_val ground_truth #> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <list> #> 1 25 15 5 3 <named list [1]> #> 2 50 15 5 3 <named list [1]> #> 3 75 15 5 3 <named list [1]> #> 4 100 15 5 3 <named list [1]>We see the four columns with problem parameters and the fifth with the ground truth coefficient vectors.

-

fixed_parameters. Here we put only the number of data realizationsBand the seed to set for the simulation.fixed_parameters <- list( B = 20, # number of data realizations seed = 4 # seed to set prior to generating data and running methods ) -

generate_data_function. We define the data-generation function as follows:# define data-generating model based on the Gaussian linear model generate_data_f <- function(n, p, ground_truth){ X <- matrix(rnorm(n*p), n, p, dimnames = list(NULL, paste0("X", 1:p))) y <- X %*% ground_truth$beta + rnorm(n) data <- list(X = X, y = y) data }Note that we extract the coefficient vector

betafrom theground_truthobject. Additionally, we need to callsimulatr_function()to add a few pieces of information thatsimulatrneeds. In particular, we have to give it the argument names of the data-generating function (typically obtained usingformalArgs(generate_data_f), as below). We also have to letsimulatrknow whether the data-generating function creates just one realization of the data (loop = TRUE) or allBat the same time (loop = FALSE).# need to call simulatr_function() to give simulatr a few more pieces of info generate_data_function <- simulatr_function( f = generate_data_f, arg_names = formalArgs(generate_data_f), loop = TRUE ) -

run_method_functions. Let’s define functions for OLS and lasso:# ordinary least squares ols_f <- function(data){ X <- data$X y <- data$y lm_fit <- lm(y ~ X - 1) beta_hat <- coef(lm_fit) results <- list(beta = unname(beta_hat)) results } # lasso lasso_f <- function(data){ X <- data$X y <- data$y glmnet_fit <- glmnet::cv.glmnet(x = X, y = y, nfolds = 5, intercept = FALSE) beta_hat <- glmnet::coef.glmnet(glmnet_fit, s = "lambda.1se") results <- list(beta = beta_hat[-1]) results }Again, we need to call

simulatr_function()to add a few pieces of information thatsimulatrneeds. This time, we need to give it all arguments to the method functions except the first (the data itself), which usually will be empty. We also have to letsimulatrknow whether the method functions input just one realization of the data (loop = TRUE) or allBat the same time (loop = FALSE).# create simulatr functions ols_spec_f <- simulatr_function(f = ols_f, arg_names = character(0), loop = TRUE) lasso_spec_f <- simulatr_function(f = lasso_f, arg_names = character(0), loop = TRUE)Finally, we collate the above method functions into a named list. It is crucial that the list be named.

run_method_functions <- list(ols = ols_spec_f, lasso = lasso_spec_f) -

evaluation_functions. Let’s evaluate the estimate ofbetausing the RMSE. To accomplish this, we define the following evaluation function:

2. Create a simulatr specifier object

This is the easiest step; just pass all four of the above components

to the function simulatr_specifier():

simulatr_spec <- simulatr_specifier(

parameter_grid,

fixed_parameters,

generate_data_function,

run_method_functions,

evaluation_functions

)3. Check and, if necessary, update the simulatr

specifier object

check_results <- check_simulatr_specifier_object(simulatr_spec, B_in = 2)

#> Generating data...

#> Running method 'ols'...

#> Running method 'lasso'...

#>

#> SUMMARY: The simulatr specifier object is specified correctly!This message tells us that the simulation did not encounter any errors for the first two data realizations. We are free to move on to running the full simulation.

4. Run the simulation on your laptop

Since this example simulation is small, we can run it on your laptop in RStudio:

sim_results <- check_simulatr_specifier_object(simulatr_spec)

#> Generating data...

#> Running method 'ols'...

#> Running method 'lasso'...

#>

#> SUMMARY: The simulatr specifier object is specified correctly!5. Summarize and/or visualize the results

Let’s take a look at the results:

sim_results$metrics

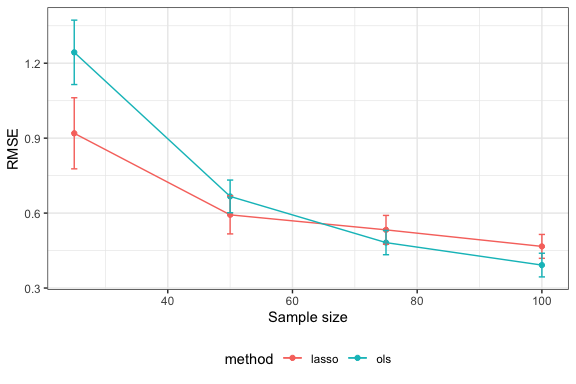

#> # A tibble: 8 × 8

#> method metric mean se n p s beta_val

#> <chr> <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

#> 1 lasso rmse 0.919 0.0711 25 15 5 3

#> 2 ols rmse 1.24 0.0644 25 15 5 3

#> 3 lasso rmse 0.593 0.0382 50 15 5 3

#> 4 ols rmse 0.667 0.0327 50 15 5 3

#> 5 lasso rmse 0.533 0.0289 75 15 5 3

#> 6 ols rmse 0.482 0.0243 75 15 5 3

#> 7 lasso rmse 0.467 0.0239 100 15 5 3

#> 8 ols rmse 0.392 0.0237 100 15 5 3We have both the mean and Monte Carlo standard error for the metric (RMSE) for each method in each problem setting. We can plot these as follows:

sim_results$metrics |>

ggplot(aes(x = n,

y = mean,

ymin = mean - 2*se,

ymax = mean + 2*se,

color = method)) +

geom_point() +

geom_line() +

geom_errorbar(width = 1) +

labs(x = "Sample size",

y = "RMSE") +

theme(legend.position = "bottom")

It looks like lasso performs better for small sample sizes but OLS performs better for large sample sizes.